Armistice Special: He Did Not Shame His Kind. By Michael Taylor – Crowborough

The 18 year old man could not see. Bullets flew all around him in the rain and shells remorselessly ripped the soil apart. He stumbled and was hit. He was never seen again.

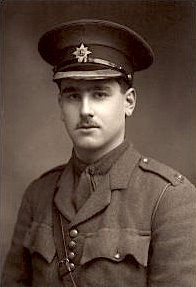

Many men met a similar fate at the hands of the Western Front during the Great War and the Battle of Loos was no exception. What makes this man stand out, though, is his name. He was John Kipling, son of the youngest Nobel Prize winner of all time and hero of British literature, Rudyard Kipling. He was also the inspiration for his father’s most famous poem, ‘If’.

If the truth be told, John should never have been anywhere near war. His eyesight was abysmal. He was refused entry into the Army for this reason on two separate occasions; once on his own and once with his father.

However, John was desperate to enlist and had been for many years. Seeing his son’s disappointment, Rudyard leant on his friend Lord Roberts, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army, and persuaded him to grant John a post with the Irish Guards.

With his father’s help, John therefore found himself a soldier and despatched to France. He joined the Battle of Loos as part of a reinforcement push, but it was already a lost cause. The British Army outnumbered the Germans by seven to one, but the enemy had the advantage of the terrain. Hundreds of German machine gun posts were hidden in the woods; the British used chlorine gas but the wind unexpectedly changed and British troops were themselves gassed; the Germans retreated but then pushed the British back and, when the British retaliation came, it had to go without artillery support and thousands of men walked into a curtain of bullets.

The men were told they were about to take part in “the greatest battle in the history of the world”. What they actually got was one of the greatest debacles in the whole of British history.

When Rudyard received the news of John’s fate, he was utterly devastated. He embarked on a mission to find what exactly happened, desperately hoping John was still alive somewhere. He organised for leaflets to be dropped from planes with John’s details and spoke to John’s fellow soldiers, but it was all to no avail.

In fact, John’s remains were not discovered until 1992, and he was buried in St Mary’s Advanced Dressing Station Cemetery in Loos. However, there is still doubt over whether the body, found two miles from where John was last seen, is actually that of Kipling’s son. Rudyard perhaps found solace in becoming a member of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission before the end of the war and chose the Biblical quote “Their Name Liveth For Evermore” to adorn the row upon row of gravestones.

Rudyard never truly forgave himself for the part he indirectly played in John’s tragedy. He wrote the poem “My Boy Jack”, a thinly-veiled ode of regret to his son in 1915 and also penned the guilt-ridden couplet “If any question why we died/Tell them, because our fathers lied”.

Comments